Greenland’s coastline is huge: a sprawling 27,394-mile labyrinth of fjords, glaciers, and ice-choked waters, longer than Earth’s circumference. Its length and topography makes it one of the planet’s longest and most logistically hostile to patrol in peacetime. Now, with countries like Russia and the United States’s neo-imperialist plans to grab as many Arctic natural resources as possible, it is one of Europe’s frontlines. Which is why people like Jens Martin Skibsted—global partner and VP of foresight and mobility at design studio Manyone—are thinking about how to better protect a wonderland that is key for the future Denmark and the European Union.

For decades, Denmark has relied on the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol (yes, soldiers using sleds and good boys), satellites, and sporadic aerial surveys to monitor this vast expanse. These methods are slow, costly, and imprecise. For example, in 2023, a tsunami in Dickson Fjord went unnoticed for a year, clearly exposing the systemic gaps in this mixed surveillance system.

Skibsted and his design team originally thought drones could be a solution. Drones are efficient, they can act in swarms, and they can be fitted with cameras and sensors that can feed an artificial intelligence system to keep track of that vast ice landscape at all times. But traditional drones have problems. The big ones are long range but expensive to operate and require human crews. The small ones don’t have enough range: Their batteries run out after a short time and they need to return to a base to reload. Skibsted and his team thought that they needed a new solution—one that could fly, so they could quickly cover large patches of territory, but also one that could operate entirely on its own, landing, recharging, and taking off again.

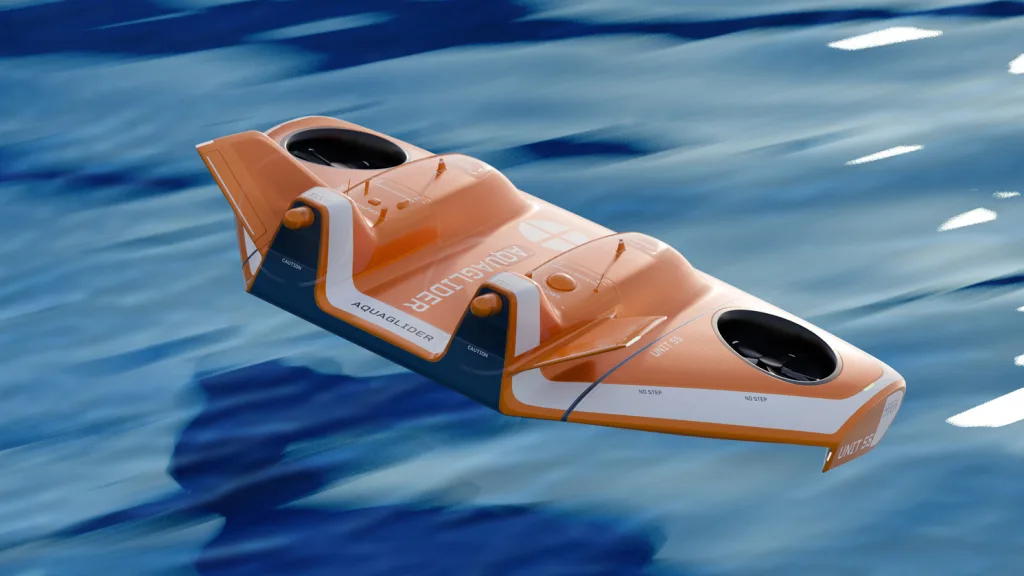

The AquaGlider, as they called their drone, is a solar-powered autonomous drone. It reimagines the USSR’s ekranoplan, a large airplane-like vehicle once feared by NATO, which the Red Army wanted to use for coastal invasions. Its origins trace back to the 1960s, when Soviet engineer Rostislav Alexeyev designed a hybrid aircraft-boat that exploited ground effect, an aerodynamic phenomenon where wings gain increased lift and reduced drag when flying within one wingspan of a flat surface. By skimming 10–30 feet above water, these mammoth craft, like the 550-ton “Caspian Sea Monster,” achieved fuel efficiency double that of airplanes, hauling military assets at 300-plus mph. Soviet GEVs were plagued by instability in rough seas, navigational hazards, and political abandonment after the USSR’s collapse.

It’s ironic that a machine inspired by Soviet ingenuity could become Europe’s first line of defense in a region where Russia is rapidly militarizing (and which Trump also wants to control). But Skibsted saw potential in this forgotten tech to create a new kind of vehicle. The proposed AquaGlider would fly on its own for weeks at a time, taking off and landing on water; it’s designed to recharge while floating thanks to solar panels, and avoids storms by simply sitting on the water rather than flying. The drones make the most efficient use of energy, dozens of them zipping along the huge coastline a few feet above the water to absorb information and transmit it to base, surveilling everything from illegal fishing to Russian submarine activity.

Engineering perpetual motion

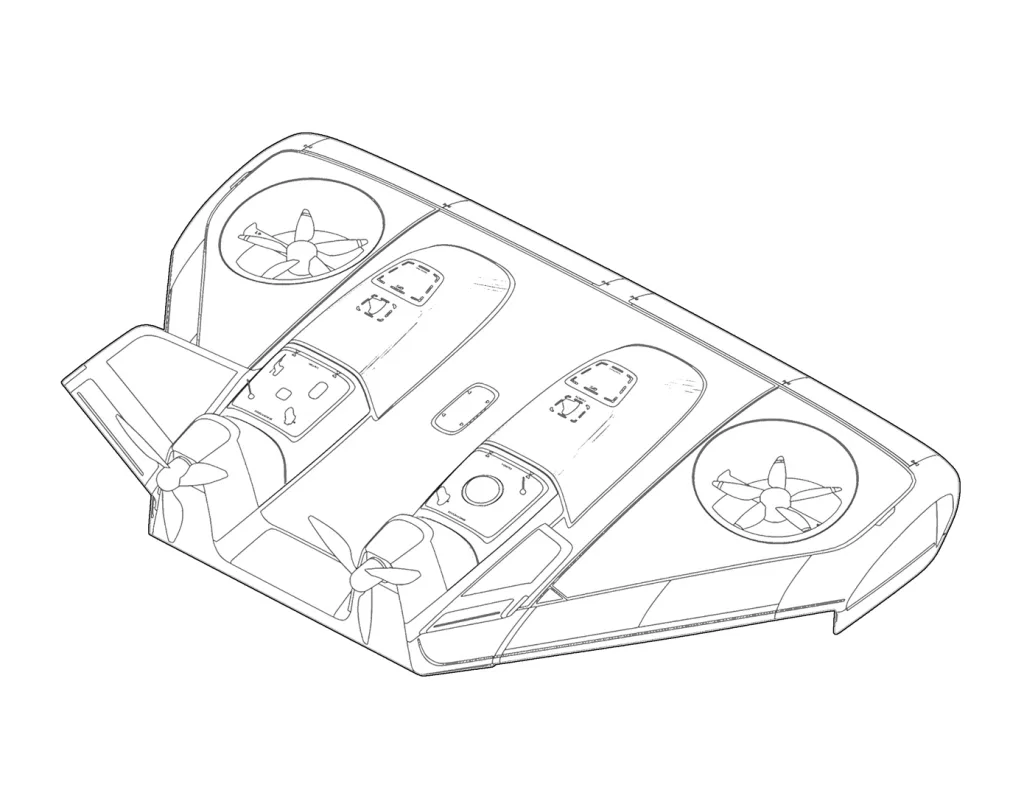

The AquaGlider is basically a wing that uses two propellers to speed forward, trapping air against the ocean or ice. This creates an air cushion that allows it to glide with minimal energy. This ground effect lets it travel twice as far as a conventional aircraft on the same power. During takeoff, retractable hydrofoils lift the hull above waves, reducing drag until the craft transitions to flight. If storms surge, electric thrusters enable vertical takeoff, though Skibsted told me in an email interview that this “zaps the battery” and is a last resort.

Solar panels cloak its wings and underbelly, harvesting energy even in twilight—a critical feature near the Arctic Circle, where summer brings 24-hour sunlight and sometimes the sun rays go almost parallel to the ground for most of the day. Still, Greenland’s winters, with months of darkness, pose a problem. Here, the AquaGlider docks with buoys that store energy from waves and offshore wind farms. These buoys double as communication relays, transmitting data to satellites or coastal stations.

Durability is baked into its graphene-coated composite hull, which resists corrosion and iceberg collisions. “It avoids obstacles like any driverless car,” Skibsted tells me, relying on Lidar and thermal sensors to navigate. For icing—a fatal flaw in Soviet designs—the drone borrows deicing systems from modern aircraft designed to work under extreme conditions, like those of Air Greenland’s he says, using heated surfaces or pneumatic boots to shed frost.

The geopolitical iceberg ahead

For now, however, after all the technical work done with an unnamed drone manufacturer that was Manyone’s client, the AquaGlider remains a design on paper. “The client aborted the project because they were too busy making drones for the Ukraine war,” Skibsted says. “So, basically we own it ourselves. We don’t know what will happen, but Denmark is investing heavily in the arctic.”

Indeed. Denmark knows that things may get really bad. Russia’s Arctic ambitions loom large. Its “shadow fleet” patrols the GIUK Gap (Greenland-Iceland-U.K.), mapping underwater cables and wind farms for potential sabotage. Danish intelligence warned that Russia could mobilize for regional war within five years, which now have been updated to just two if NATO appears divided, according to Troels Lund Poulsen, the Danish defense minister: “Russia is likely to be more willing to use military force in a regional war against one or more European NATO countries if it perceives NATO as militarily weakened or politically divided.” In response, Denmark’s 2024–2033 defense agreement has committed $570 million to maritime upgrades, including autonomous drones, underwater sensors, and 21 new Home Guard vessels.

The AquaGlider fits neatly into this strategy—a low-cost, persistent patrol akin to Ukraine’s low cost maritime drones, which have destroyed or damaged at least 26 Russian naval vessels in the Black Sea since the war began including the Red Navy’s Moskva flagship. But Denmark’s immediate investments are pragmatic: four minelaying ships and underwater drones will deploy by 2030. But there’s also a section of the budget that will be dedicated to “autonomous surveillance crafts that can monitor the coastlines,” Skibsted tells me. That’s where AquaGlider can fit. It makes sense from a design perspective. It will be up to the engineers to make it a reality, if it picks up the interest of the Danish government.