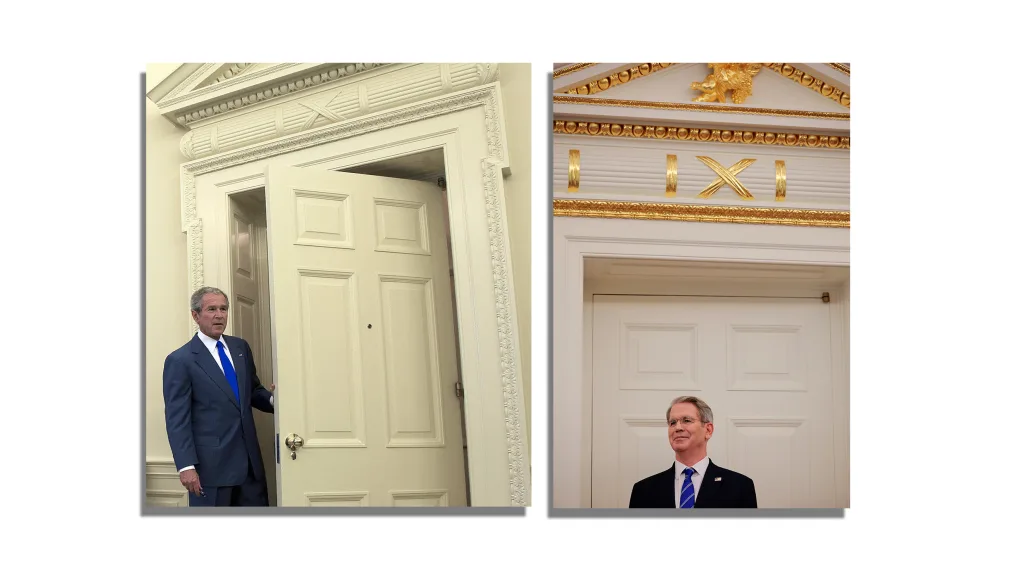

Given President Donald Trump’s well-established penchant for golden objects, it was not a surprise to many when images of his administration’s decorative choices in the Oval Office started appearing.

The space now abounds in gold. There are gold picture frames, gold statues, gold trophies, gold crown molding, and gold coasters. The Wall Street Journal reported that Trump called in his Mar-a-Lago “gold guy” to assist with the redesign, adding custom-made and gilded carvings. Compared to those of presidents past, Trump’s Oval Office decor is a maximalist and glistening tour de force.

To some, the decoration is all a bit much. New York magazine called the overall decorative approach in the White House “tacky and trollish.” An opinion piece in The Washington Post called the decoration “gaudy-awful.” Another drew a direct line between Trump’s decorative leanings and the over-the-top opulence of the Palace of Versailles.

“In order to gain a certain kind of reputational notoriety he emulates this style that’s connected with the elite. But he does so in a very pastiche way,” says Robert Wellington, a professor of art history at the Australian National University and a specialist in the arts in France during the reign of Louis XIV. Trump, who has called “the look and feel of Louis XIV” his “favorite style,” has interpreted this period mainly through items that are, or look like, gold. “Perhaps he’s trying to create a sense of material splendor around him that gives a sense of power and buttresses his claims to the success that his administration is having,” Wellington says. “He wants to give that illusion of success.”

What are those things?

According to information from the White House, some items in Trump’s Oval Office actually do have legitimate value, both materially and historically. On top of the mantle, there is a line of seven historic items from the White House collection dating back to the early and mid-19th century.

This is the lineup, according to details from the White House curator’s office, that was provided by a source in the White House. On the outside edges there are two gilded silver dessert stands made around 1810. Next to those are two gilded silver figurative centerpieces made around 1843. Next to those are two gilded bronze vases made around 1817 and associated with James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States. And in the center is a gilded bronze basket made between 1815 and 1820. All the items originated in either England or France.

The provenance of these pieces may have some subversive significance for those who read between the lines. The four outermost pieces were bequests from Margaret Thompson Biddle, heir to a diamond- and copper-mining fortune and one of the richest American women of the mid-20th century. Once married to a diplomat, she lived for many of the pre- and post-World War II years in Europe, and hosted famous salons in her Paris home with the leading lights of American and French society.

The centerpiece was a gift of Gifford B. Pinchot, an early trustee of the Natural Resources Defense Council, an organization that by its own accounting sued the first Trump administration 163 times. Pinchot, who donated the piece in 1973 and died in 1989, was the son of Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the U.S. Forest Service and a close ally of Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th U.S. president, with whom he helped formulate the federal government’s approach to resource conservation. Neither of these people would seem ideologically connected to the current administration’s policies.

Made in the USA? Not in the White House

More notable, perhaps, is the fact that none of the items on the mantle in Trump’s Oval Office were made in the U.S., which contrasts with the administration’s present focus on imposing tariffs on foreign-produced goods and services.

“There is a long passion for French decorative arts in America, through the Gilded Age patrons but also in the White House itself. So it’s not completely outrageous to imagine these French styles coming into the White House,” Wellington says.

But Wellington also sees a deep irony in Trump’s affection for Louis XIV and the Palace of Versailles, which he explores in a forthcoming book, Versailles Mirrored: The Power of Luxury, Louis XIV to Donald Trump. Wellington notes that Versailles was built as a kind of advertising program, establishing France as the center for luxury production by putting its finest craftsmanship in furniture, metalwork, mirrors, silks, and paintings on display. The palace’s decorative approach was also a form of protectionism, meant to stop people from importing luxury products from other countries. “It was state-sponsored luxury production which led to France being seen as the place where the very finest things could be made,” Wellington says.

Trump’s version of Louis XIV’s approach is more surface than substance, Wellington says. In contrast with the industry-boosting decoration at Versailles, the White House decor undermines one of the administration’s key policies. “If Trump wanted to be a Louis XIV, I think he would be well placed to support the arts and culture. Instead, there’s very regressive ideas about arts and culture being supported under the Trump administration,” he says.

“To be a great model of patronage you would be looking to the greatest minds of the day, the greatest artists of the day to create an image of America, to make America great again,” Wellington adds. “The way that you would do that is to think to the future, not to lock into some old idea.”